With CAN AND CANDOR

- Jordanian graffiti artist paints her way from city walls to global activist -

The afternoon slips into dusk and Laila is still at it, spray can in hand, hunched forward, confined by the cage of a crane that holds her twenty feet in the air as she perfects the shapes of her mural. At least, this is how I imagine Laila Ajjawi, feminist graffiti artist, at her first Women On Walls exhibit - an event that not only put Laila's graffiti on city walls but on the international radar as well.

Women on Walls is an art initiative launched in Egypt and the Middle East that uses graffiti to talk about womens' rights. Ajjawi, one of its early contributors, was born and raised in a Palestinian refugee camp in Irbid, Jordan.

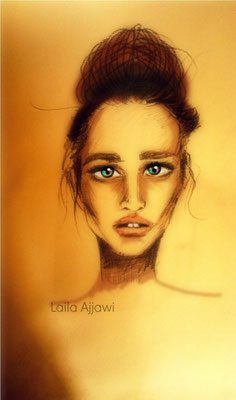

Ajjawi has been doodling, drawing, and painting since she was nine years old. Today, the 25 year old artist uses graffiti to take public issues back to the public space. Instead of processing social issues in privacy, graffiti art puts it back in the social world, forcing passersby to address them head on.

Irbid Camp, home to approximately 45,000 refugees is a roughly 57-acre space where generations of Palestinians have lived since fleeing Palestine during the onset of the 1948 Arab Israeli Conflict. An estimated 700,000 people either fled or were forced from their homes. Crowded camp Irbid is in the northern tip of Jordan, nestled in Irbid Metro. Irbid's hot mediterranean climate is a major transportation hub, including five major universities, and a seemingly endless sea of structures nestled in an arid valley. Ajjawi and her siblings were born there, in a camp just outside the city, as were her parents after her grandparents: two of the 700,000 that fled during the conflict.

After her experience with Women on Walls in 2014, we find Ajjawi back in Irbid, can in hand, advancing the cause of women in her own community. Consistent in her work are themes of women's empowerment in a male dominated society. Ajjawi's work reminds us of the legal and social crosshairs that have got women pinned in subservience.

Though there are many educated females in Jordan, the country has one of the world’s lowest rates of female participation in the workforce. Only 16 percent of Jordanian women participate in the economy. Social norms prevent much of a change to this status quo.

Violence against women is prevalent and often go either unreported or unpenalized. The Rape Law, or penal code Article 308, makes it so that all rape charges are dropped if the culprit marries the victim. Additionally, only Jordanian men can pass their citizenship to non-Jordanian spouses and their children. Also, a woman cannot file for divorce without "evidence" for its necessity unless it is filed in accordance with her husband, or she loses the right to any financial support.

Despite the growing interest in women's rights in Jordan, changes aren't coming quick enough for Ajjawi. Her goal is to inspire other Jordanian women to take control of their own lives despite legal or social opposition.

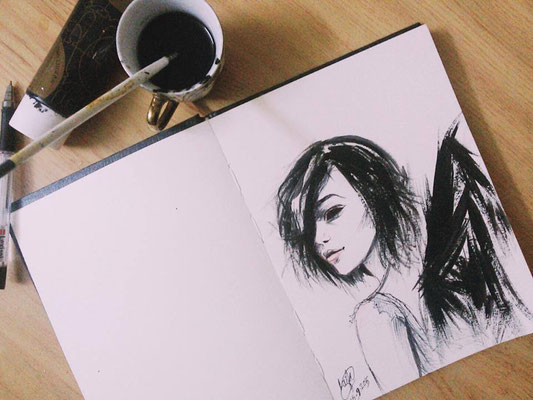

Waking up in a crowded home she shares with her parents and 5 siblings, Ajjawi has no place to store her art supplies, or a room of her own to dream up her next mural. Storing these images in her sketchbook and her head, Ajjawi gathers her belongings and ventures out of Irbid camp into the greater metro area in search for a derelict wall.

Street art is usually a male dominated enterprise in the Middle East. By breaking this trend and painting about women's related issues, Ajjawi's aim is to encourage women in her community to be "decision makers" and to transcend social and economic stigmas.

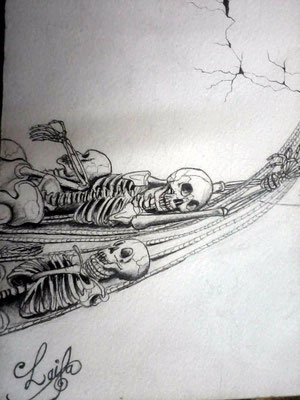

The messages in her murals aren't aimed to criticize men but to encourage women to re-evaluate their self-image. The mural entitled "Look at My Mind" features a woman's head cracked open, revealing a bird that has broken from its cage, a flower reaching for the sky, waves of water and a rainbow, among other things. All of these images spilling out of the head as if the sheer force of them had caused the woman's brain to burst at the seams. Ajjawi tells us this image is for women who are negatively influenced by media's beauty standards. It is for women who have forgotten the "unique beauty and charisma that each girl has." However, it's also for men, who she says are also victims, and may have been equally "brainwashed" by these principles. Laila is careful to illuminate issues in society without pointing blame at either gender.

Other of Ajjawi's murals have focused on issues of street harassment, gender-based violence and political resistance. Ajjawi's early influences include Manga and cartoon fictional characters with a realistic and cutting edge twist. In her more recent work; however, we see a surrealist style emerging, an art movement fueled by the belief that the psyche has the power to reveal contradictions in the everyday world and spur on revolution.

To learn more from the source, we sought an exclusive interview to shed light on her experience with future projects, romance and Jordanian politics.

// Despite the growing interest in women's rights in Jordan, changes aren't coming quick enough for Ajjawi. Her goal is to inspire other Jordanian women to take control of their own lives despite legal or social opposition. //

Interview with Laila Ajjawi

M: Tell us about your first experiences with Graffiti art.

I never thought I would be able to handle the spray can! I thought it was "men's work." I was initially a fine-artist and a humanitarian aid worker, handling tiny brushes and canvases that never exceeded my length! Now I'm reaching very high heights and handling walls that are often 10X my size. The fact that my feminine touch appeared strongly within my graffiti artwork was a new discovery to me!

What has it taught you?

I remember that I never limit my self. I always seek to get to know myself more and more, and believing that I have unlimited powers within, no matter where I came from! I came from a Palestinian refugee camp known for hard conditions and poverty. My family started their life from zero and beneath. I don't have a bed or a private place. I dreamed about my 1st laptop for seven years and got it 3 years ago. I had that seed by my parents of building myself from nothing. NEVER let people tell you who you are, or what you should become, or limit your size. YOU are the only one in life who decides what you are going to become, and what is your destiny.

The Women On Walls mural theme was about Street harassment. What kind of street harassment did your mural specifically refer to?

It was about sexual objection and the fact that global media takes advantage of it in commercials, movies, TV, etc. They all focus on her body, and even portray slandered beauty sizes to serve the cosmetic industry. They make it so that the main goal for girls is to reach those standards, causing young girls to attach their self esteem with appearance. They ignore knowledge, personality, and the unique beauty and charisma that each girl has. It's to satisfy boys who are victims of those brainwashed principles.

How would you describe your artistic style? What styles influence you?

What makes my touch so clear is inserting characters within my graffiti. Usually my characters are inspired by the surrounding society. I add their identity within it, followed by a word or a sentence focused on motivation. Sometimes it is without words, to encourage others to widen their horizon.

You atteneded Yarmouk University and studied Biomedical Physics. Are you interested in pursuing professional work in this field?

I'm interested in science since the first grade. I used to go to my school's library and the public library to read and enrich my knowledge of the scientific world. I used to bring home Scientific encyclopedias I borrowed from libraries to read them at home. I always wanted to know some secrets or mysteries in the world that can't be explained except by physics: especially electromagnetic electricity and Quantum mechanic, Biomedical mechanics specifically.

Later on in secondary school, I chose science as a major. Later, I attached to the virtual world and 3D animation. I found that private universities with a focus on 3D animation costs a lot: a huge amount of money that I could never afford and it was too far from home. I then wanted to study fine art at a public university because it had one class or two in 3D animation. But it also it costs a lot. I never pushed the idea on my family. I know very well their financial struggle and I took responsibility at an early age.

But as a career now, I took a completely different path in the humanitarian response to the Syrian crises. It's better than the governmental sector but with only short contracts and the possibility for the funds to stop.

Has your humanitarian work with Syrian refugees at the NGO inspired any artwork?

It has widened my knowledge of social life and humanity. This gives me a deep dimension into my artwork.

Irbid Metro is the second largest city in Jordan. The camp Irbid is home to 25,000 people located in a 57-acre space. What is daily life like in Irbid camp compared to metropolitan Irbid?

Currently, there are approximately 45,000 people or more living here. The main struggle is the high population and the small houses. It's a very, very crowded space and there is no play area for children so the backstreets are the main space for them. Personally, I don't have privacy (private room to sleep in) or a place where I can keep my tools and artwork in one place.

What prejudice and stereotypes do you feel that you and/or your family face?

The stigma of being from a camp! There is some kind of social stigma that looks at people from a camp as a bad person and a trouble maker.

How does public art allow you to take claim of your own life? How does it inspire others?

Art in the middle east as a career is so weak because of the disturbance of the region. There is no possibility for an artist to depend on art for living. As I explained before, my main income source is from working in the humanitarian sector, and now I'm a site supervisor in a refugee camp. I have 3 years experience in the humanitarian field.

Public art is a personal tool to express what I have within my mind, and I do it because it is a necessity in my life. I get offers from some NGO's to use my art as a public tactic to raise awareness about certain issues. These offers may happen 3 times a year, and I may do some pieces for free if the campaigners can afford tools. Sometimes I use what remains of materials to do it.

It inspires others more than I expected. It alters from the regular goal of graffiti that focuses on entertainment and personal expression. I take public issues to the public space.

You, your siblings and your parents were born and raised in Irbid Camp, Jordan after your grandparents fled Palestine in 1948 during the Arab-Israeli conflict. Do you include elements or images of Palestinian culture in your art-graffiti or other art? Do you worry that people of your generation and beyond will know less and less about Palestine's history and culture?

Inside the camp, yes I include elements related to the Palestinian case. I want the new generation to stay connected to the right of our stolen land. Yes, that's true that future generations are likely to know less about it. Global media works hard to make new generations question, What is Palestine? I cannot reveal what I have for this until it's ready.

What are your views of "homeland" having never been to back to Palestine?

It doesn't matter where I've been born or raised or what is my origin. Even when I'm here, I'm a good Jordanian citizen. My homeland is a place I never been, and the thought that my life would be different if I was living there encourages me to fight to get it back for all the martyrs who have been killed defending their own land or just refused to leave their homes! For being forced to leave their homeland, my grandparents had to fight a lot to simply live. It would be awful if new generations didn't know the history, or did not try to get back the homeland.

You mentioned that you "need someone who can see [you]. . . Not just a wife or a housewife to continue others' dream," That you "want someone who has got his own dream. And at the same time, he doesn't step on [you] to go with his dream. I want to go side-by-side." Do you see any role models for this kind of partnership in your community?

There are only a few people I've known in my whole life where both had worked together to achieve their dreams. With most of the people I see, one of them takes the credit the other stays in shadow or just stops doing what ( he/she) does. This is not just here: You can see it clearly with celebrities and public figures around the world. Me and my partner want to create this model even though we both have different goals and common interests. We still can work side by side as one completes the other.

You and your fiance plan to live in Saudi Arabia, a place that is very conservative about women's behaviors. Do you think this will affect your ability or desire to develop as an artist or a public artist?

Regarding Saudi Arabia, I hear that a lot. And people keep cautioning me from going there. But what people don't know is that Jeddah is one of the biggest cities in KSA and is a core for the art movement. I already built connections with artists there including Girls! Yes, there are female artists and graffiti in specific, even famous art galleries.

Most female graffiti female artists are know nationally but not as internationally famous as I am - This is because they are doing graffiti for the sake of entertainment and not for public change. Also, women in Jeddah have less local social rules that the rest of KSA. In Jeddah, there are only the national laws that need to be changed, and I believe this change has started slightly.

In your opinion, what does public art like graffiti do that other art forms cannot?

Graffiti is the creation of an image; and, an image is a thousand words. Images are a part of the media that take many forms such as TV, radio, photos, sounds etc. Using many tools, an image that is shown to the public has a wide effect. It can provoke certain ideas or conversation. Public space is for everyone. That's why I see the creation of a public element having to take on many responsibilities. It's owned by and belongs to the public of all ages and backgrounds of the local community.

So, whenever I do graffiti, I take all that in consideration. I do my best to create graffiti that belongs to the community: to represent their identity and speak to them more closely. The graffiti shares an idea and forces them, by the energy inside of it, to stop, look, and re-think content that reflects social issues.

Often times these images bring ideas to the public in controversial ways. Does your community or other communities think you are controversial?

Yes, but not in a negative way. Sometimes if I am near one of my public art pieces after I finish, I hear people stop by and start talking and making a conversation. It's so amusing hearing what

the public says about my work.

What murals are you planning or working on now?

Right now I'm thinking of one on a big scale to do in the camp that encourages people to dream beyond. . .

What would be your ideal project if money, travel and resources were not an obstacle?

I would focus on neglected areas, and neglected places where youth there don't take advantage of opportunities because of the hard conditions. I want to tell them with my art "Don't let conditions make you! instead you make your conditions" and motivate them to rise above.

Laila Ajjawi is a graffiti artist in Irbid, Jordan

Instagram: @lailanajjawi